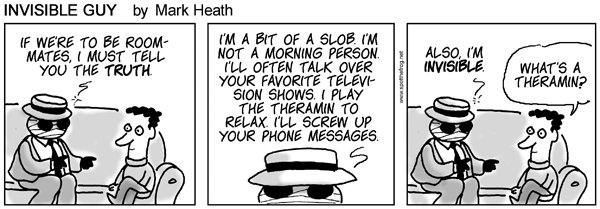

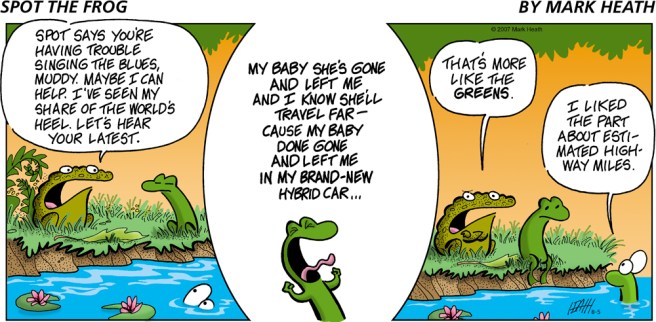

I used to shade my cartoons with markers. It felt like a cheat — rather than shading with a brush or pencil or charcoal, as did most of the cartoonists I admired, I’d uncap a marker. There were tricks to learn — working different shades of gray into the marker ink before it dried, for example — but it lacked the panache, the reverence, of mastering a traditional wash.

And though it was a cheat, it still had its demands. I had to work fast, to achieve the wet-on-wet look I favored. I had to estimate the bleed of the ink to honor boundaries. I had to be ready to grab a replacement if a marker died in the thick of shading and became a shade itself.

When I finished and reeled back in my chair (swooned is the better word — working close to the paper, my nose breathed a fog of delirium) I felt like Lloyd Bridges lost in an underwater cave, breathing toxic fumes — not from a scuba tank, but a gigantic marker tube… talking to myself … narrating… imagining that I had an audience.*

I was Lloyd Bridges as David Copperfield as Mark Heath. The Hero of my own story.

This was before I used a computer. This was before Photoshop. This was before scanners. This was the 80’s and early 90’s. In terms of technology, I was living off the land, building cartoons with anything I could find that was cheap and plentiful, mostly office supplies.

I use Photoshop now. I don’t miss the markers. They were high maintenance. Not on a par with cleaning a dip pen, or coddling a camel-hair brush, or sculpting a pencil tip. But If I forgot to cap a marker**, the nib died, became a husk, as dry as a mummy. My desk drawers rattled with the sarcophagi of dozens of markers. Some were premature burials, on the threshold of shading their last. Every month or so I’d ransack a drawer, violating caskets, on the chance that a long-capped marker had transitioned into a second life.

On the other hand, if I remembered to cap it***, and the nib seemed fresh, it wasn’t unusual for the ink to sputter in mid-wash and cut out like a plane with an empty tank, spiraling with a mounting groan (my own) into the paper, ending in either an ugly blotch, or scraping across the sheet and carving a ditch.

But that’s me. If you’re feeling nostalgic, or enjoy a flight metaphor, or appreciate the comic work of Lloyd Bridges, Mark Anderson offers a flying lesson.

*Much like blogging.

**And by if, I mean when.

***And by if, I mean if.